The TEXTILE INDUSTRY can be divided into two basic parts according to the use of the manufactured product: textiles for personal use – for clothing, home use and leisure – let’s call it consumer textiles, textiles for use in industrial and special fields – automobile production, construction, health, hygiene, agriculture, aerospace and other fields – we call it technical textiles. Ever since people made the first textiles, they wanted to improve them, to decorate them. Various decorations up to hand printing were also used in our country and gradually dyeing and printing of textile materials was applied. At first by hand and about 200 years ago, the printing of textiles by industrial methods was introduced.

The basic technological procedure of printing – preparation of fabric, printing with some printing technology, drying, steaming and washing. In the case of pigment dyes, only fixing or fixing the dye to the fabric was carried out. The fabric was then treated.

Perotina mechanized hand printing with moulds. The design was transferred onto the fabric by narrow rectangular moulds across the entire width of the fabric at once. In the Czech lands, perotinas appeared on a larger scale as early as 1838 in Prague and Josefův Důl in the Mladá Boleslav region. They were used in the Královédvor region in the second half of the 19th century. After World War I, these machines disappeared, giving way to the mass appearance of cylindrical printing presses. The printing moulds were made of wood with an elongated rectangular shape. The wood was engraved with a patterned relief or embedded with all-metal wires, plies or a combination of both. The production of the moulds was very labour intensive. The propulsion of the perotines was initially by human power. The machine mechanised the movements of the printer during hand printing and, in addition to replacing 50 hand printers, was also characterised by its precise work result. Perotines became a symbol of the hated machines because they “took” the work of hand printers who began to resist. The most violent protests took place in the Prague cartouches in 1844 and were also carried over to the Mladá Boleslav region. There were also machine smashings. The army was deployed and the resistance of the workers was broken. However, progress could not be stopped. This time is also commemorated in the well-known work by Jakub Arbes, “Štrajchpudlíci”.

A successful pattern (design) is decisive for the prosperity of a textile printer. It consists of an interesting motif, matching and attractive colours, the right fabric and its final appearance. Each printer had its own design centre. Between 1949 and 1992, the Institute of Furnishing and Clothing Design set the trends in the country.

Dvůr Králové nad Labem has been a centre of textile printing since the beginning of the 20th century. At first, printing was carried out in a number of private printers and after nationalisation in the factories of the national enterprise TIBA, which was transformed into a joint-stock company after the revolution. TIBA had up to 5,000 designs in its collection, about half of which were renewed every year. The rich history of the textile pattern is preserved in the pattern books.

From the patterns created, a so-called “tender collection” was created, which was usually offered four times a year or was created continuously. Sample pieces were printed and handed over to the sample department. There, skilled women cut them and created sample material for customers. The so-called mitams, which was a printed pattern hung on a hanger, served as the basis. You had to see a repetition of the pattern (raport), which was not a problem with smaller motifs. But later, for large-scale ones, especially for bedding, a large amount of pattern material was used. The sample material was sent to foreign trade companies, such as Centrotex, and important customers. The creation of the collection was one of the most expensive processes of print production.

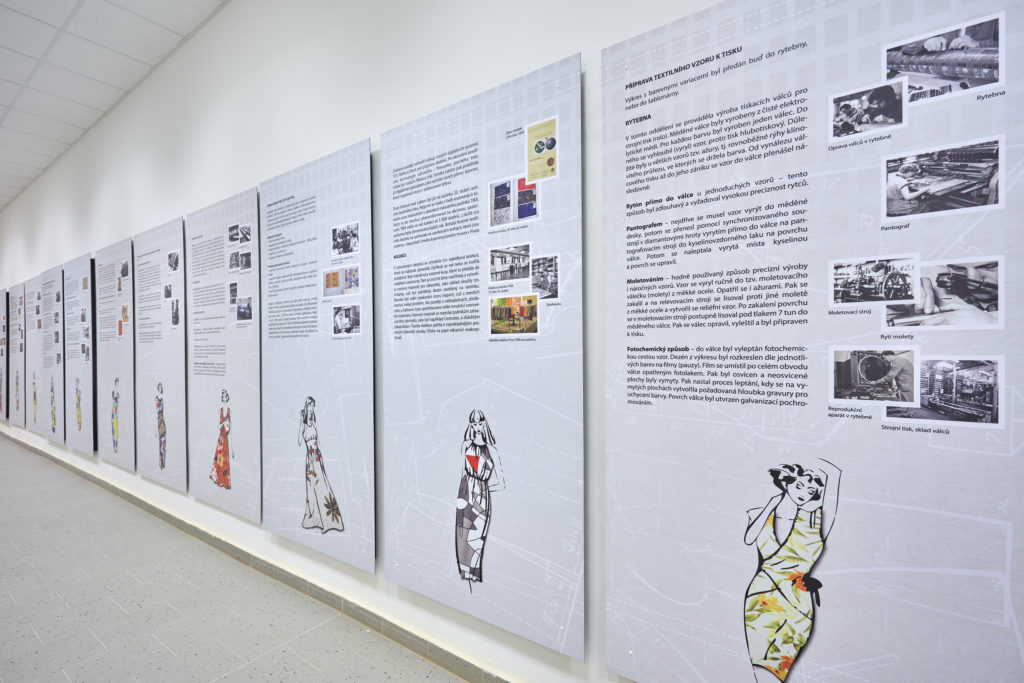

Pantographing was a method of transferring a pattern to a cylinder suitable for large, coarser patterns without fine detail. The engraver and the pantographer worked together. The engraver transferred a drawing of the report drawing at three to five times magnification onto a zinc plate about 1 mm thick. The pantographer fixed a printing cylinder with a layer of acid-resistant varnish on the surface into the pantograph. He clamped a zinc plate with the engraving on the scanning table. He ran the engraving in the plate through the scanning tip at one end of the swinging lever on the pantograph. Each movement of the stylus was transmitted in appropriate reduction to a series of diamond styli at the other end of the gear. The nibs engraved hints of contours and openings in the lacquer layer at the required size. The number of nibs corresponded to the number of reports across the width of the fabric. The cylinder jacket was then etched, and where the acid-resistant coating was broken by the nibs, an engraving of the design was created, where paint was later applied. After the necessary cleaning, the cylinder could be used. Pantographing was easier, faster and cheaper than milling. However, the durability of the etched patterns was low. Mechanical pantographs were later replaced by photoelectric devices.

Moletting made it possible to create an intaglio pattern in the printing cylinder, which was characterised by high durability. It was mainly used for fine patterns. The molet engraver, the relever and the molet maker worked together. The molet engraver engraved the master molet (a metal cylinder with an engraved design). The relever pressed the embossed molet (the pattern was above the surface of the roller) in the relever. With it, the molder then pressed the pattern into the soft copper surface of the printing roller in the molting machine. The actual milling took place on the milling machine under constant high pressure. The molleteer rolled the embossed mole over the surface of the printing cylinder until the engraved areas were sufficiently molded into the so-called mother mole. The moleta had a width corresponding to the width of the report area, so the surface of the cylinder was moletized gradually. After the pattern was finished being pressed into the cylinder, the cylinder was repaired, finely sanded and polished. The surface of the cylinder was then coated with a resistant metal, e.g. chrome. The cylinder could be used for a long time. The profession of a molet engraver was one of the most demanding in terms of precision.

In film printing, the dyes are pressed onto the fabric with a squeegee through holes in the stencils (screens). Film printing is therefore also called screen printing. It is still used today not only in textiles, but also in printing other materials – plastics, paper, porcelain, glass, wood.

Film printing, otherwise known as screen printing, appeared in ancient times in Asia. However, its industrial development did not occur until the 1930s. It was printed by hand using a flat stencil and a squeegee. One stencil was designated for each colour in the design. The exhibit shows part of the printing table on which the fabric was printed with flat stencils. In the second half of the last century this technique was used in several Czech printers. Today it is used only in small workshops or cooperatives. The printer glued the fabric to the smooth surface of the table. He placed the stencil on it, poured the ink onto the edge of the screen and with a few strokes of the squeegee pushed it through the etched holes in the varnish applied on the screen onto the fabric. He then lifted the stencil, moved it the length of the report so that the pattern followed exactly, and continued printing. For larger widths of fabric, there was a helper on the other side of the table. After printing, the fabric was carefully removed and hung to dry. The development of flat stencil printing also contributed to the collaboration between textile printers and artists. In the 1930s, artists such as František Kysela, Alois Wachsmann, Antonín Kybal, Karel Svolinský and Josef Čapek worked for the Sochor company in Hanover. In the 1960s, hand printing with flat stencils was fully mechanised. The arduous work of printers was eliminated and the productivity of work increased greatly. However, this method of printing was quickly replaced by rotary film printing.

In machine cylinder printing, dyes or chemicals were applied to predetermined places on the textile using either embossing rollers (printing from height) or engraved rollers (printing from depth). Embossed cylinders were all-wood or in combination with brass or steel. The machine was mainly used to print large quantities of textiles with fine and small patterns. The basic printing unit consisted of a copper cylinder into which the design was engraved and then hardened with chrome. One cylinder was designated for each colour of the pattern. All the cylinders of the pattern had to be so called reprinted by the printer, i.e. all the colours were exactly aligned in the pattern. This type of printing brought high productivity and accuracy, but was demanding to operate. After printing, the fabric was dried in a drying chamber (attic). This was followed by steaming to stabilize the printed dyes and washing to remove excess and unfixed dyes.

The cradle of blueprinting is South and Southeast Asia. Blueprints were brought to Europe by Dutch traders in the mid-16th century. The great demand for imported blueprints led to the later establishment of blueprint workshops and manufactories on the European continent, also in Bohemia in the mid-18th century. Only two workshops are still in operation in the Czech Republic, in Olešnice and Strážnice. Blueprinting was initially done by hand using wooden plates with carved relief. When the demand for blueprints increased, the production was switched to perotina and later to cylindrical printing machines. The moulds for blueprinting are still produced by local residents- Milan Bartoš and Jaroslav Plucha. On 28 November 2018, the blueprint was added to the UNESCO Intangible World Heritage List. The blueprint is the best known type of reserve (negative) textile printing. Blueprint designs are created by applying a reserve mixture – pap (pop) – in the form of a blueprint on a usually bleached, thoroughly washed, starched and starched textile. The mixture prevents the colour from penetrating the textile when dyeing the fabric cold in an indigo bath. The parts of the fabric not covered with the reservative mixture will turn blue when removed from the vat (after the dye has oxidised). The saturation of the blue colour is determined by the number of times the fabric is soaked in the vat, or removed from it, associated with the oxidation of the dye. By soaking in a weak sulphuric acid solution and washing in water, the reserve mixture is removed from the dyed fabric. The pattern remains white. After the blueprint has been developed, the blueprint fabric is mandelled, smoothed or ironed.

Contact to the exhibition:

Adresa: nábřeží Jiřího Wolkera 132, Dvůr Králové nad Labem

Phone: +420 730 141 819

E-mail: textil@muzeumdk.cz